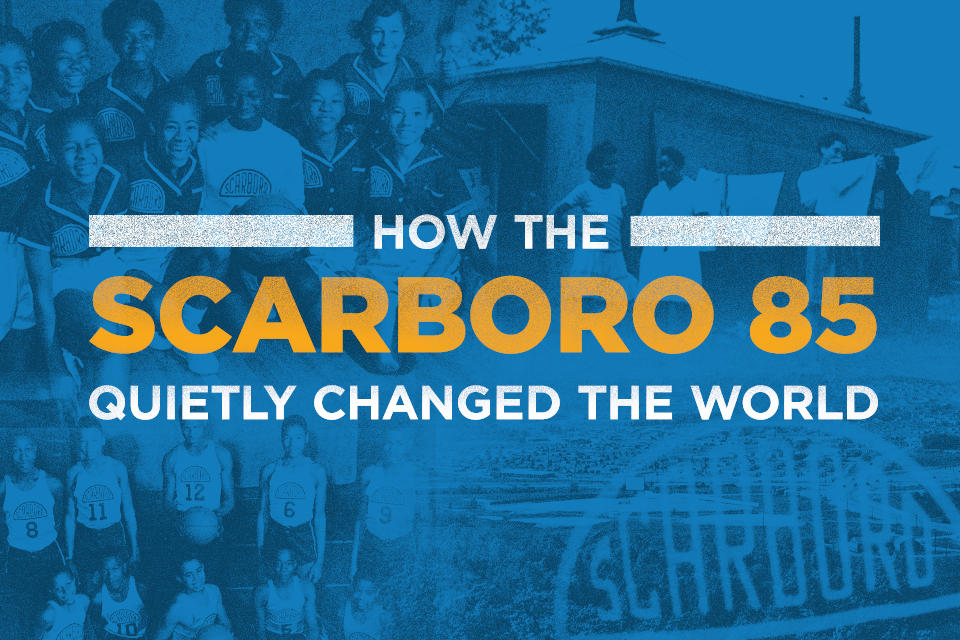

Scarboro 85 members quietly made history

They were just children - high school and middle school students - thrust into an often painful and volatile national debate: the integration of our country’s public schools.

On September 6, 1955, only a year after the landmark United States Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education, 85 Black students from the Scarboro community walked into two then all-white schools - Oak Ridge High School and Robertsville Junior High School - and bravely broke a barrier as old as the country.

The occasion was met with some hostility, but no violence. The students will tell you they were harassed and called names, but the color barrier had been broken without major incidents. So quiet was the transition, it received little national attention. That would be reserved for later, in other parts of the South.

Many Oak Ridgers have known little about the integration efforts, but that is changing. The Black students who challenged the status quo are now known collectively as the Scarboro 85, and there are efforts underway to tell their stories to a larger audience.

“The Scarboro 85 don’t get the credit they are due,” says John Spratling, vice president of the Scarboro Community Alumni Association and a fifth-grade social studies teacher at Robertsville Middle School.

“In 1955, 85 brave, young Black students were the very first to enter all-White public schools in the Southeast,” he said.

Until recently, little has been mentioned of the events that took place in Oak Ridge in the fall of 1955. Oak Ridge’s story was overshadowed in the coming years by violent confrontations, political power plays, or even bombings in other communities, where change drew headlines.

Spratling points out that the Scarboro 85 integrated the Oak Ridge School system 5 years before 6-year-old Ruby Bridges became the lone Black student to integrate William Frantz Elementary School in New Orleans. Oak Ridge’s integration happened 2 years before the Little Rock 9 were initially turned away from an all-white school by national guardsmen and faced a cursing, hate-filled mob. Oak Ridge’s desegregation even came a year before 12 students faced anger and threats of violence while entering a previously all-white school in nearby Clinton, where a firebombing took place two years later.

Spratling also says the pioneering Oak Ridge effort happened months before Ms. Rosa Parks and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. rose to national prominence in the Montgomery bus boycott.

“Yet with all these major civil rights milestones, nowhere is the Scarboro 85 mentioned. This cannot be. They must get their rightful place in civil rights history,” Spratling said.

Spratling and others in Scarboro, a historically Black community in Oak Ridge, are making their voices heard over what they feel is an injustice not only to the Scarboro 85 but also to civil rights history. Spratling believes those Black students were “true American heroes” and he is determined to get their story out.

Spratling is a member of a group of Oak Ridgers who have begun raising funds for a permanent monument tol honor the Scarboro 85 in Bissell Park. It is a major effort, but if successful will provide a permanent record of the accomplishments of a group of young Black children who, in Spratling’s view, changed the world.

“Because of them, I am who I am. Without their sacrifices, I would not be where I am today,” he says.

A fundraising luncheon will be held on February 23 at the Doubletree Hotel in Oak Ridge, with civil rights leader Reverend Dr. Harold Middlebrook speaking. Consolidated Nuclear Security has supported many Scarboro events over the years and is proud to participate as a sponsor of this important event.